A decade or two ago, getting a custom part manufactured required you to have your own workshop or to make a visit to a factory floor. Today, you can create your own 3D model, upload it to a website, and have a functional product delivered to your door within a few days—a turn around time unimaginable just 20 years ago.

While most news about the 3D printing industry focuses on advancement in hardware and materials, software has played a crucial role in the democratization of 3D printing. Companies like Shapeways have delivered software to generate 3D files, prepare and optimize them for printing, and manufacture and distribute.

Shapeways’ primary technology offerings can split into two categories—the ability to upload, repair, price, and purchase 3D models in a variety of materials, and back-end systems driving the manufacturing, distribution, and fulfillment of our orders at a global scale. I’m going to discuss three distinct pieces of software that occur in separate steps in the buying process: one that help customers upload designs and make purchases: Model Processing; one that securely shows the customer the final printable model: ShapeJS; and one that helps us manufacture, distribute, and fulfill those design purchases: Inshape.

Processing customer models

Our first contact with a customer’s order is when they upload a 3D model. We have no control over the quality and printability of the model, so our software repairs errors during model generation where it can and analyzes their printability in a wide variety of materials. This is a very compute-heavy process—we calculate the model surface area and volume, determine the number of parts that the model is composed of, and examine the model for errors and attempt to repair them, all within a mean time of 25 seconds.

In order to deliver these results, we needed to build a system that leverages parallelism and provides easy scalability to handle fluctuations in load without breaking our SLA. To start, we decided to build individual services that are each responsible for evaluating different components of printability. These services fall into three categories: model validation, model pricing calculation, and model repair.

Model validation services are charged with validating that the model can be printed in the first place. These checks make sure that the file is valid, that we can process it, and that the model is manifold—water-tight. Pricing calculation services are responsible for generating pricing components of our models, including but not limited to volume, part count, and surface area. Finally, fixing services help us repair our customer models and ensure that they’re printable. This includes steps like repairing meshes, decimating models to reduce triangle counts, and fixing inverted matrices on the model.

Some of these services generate new files to facilitate printing, production, or image display on our site. These services are mostly implemented in Java (the language of choice for our 3D tools team), though some have been re-implemented in CUDA to run directly on GPUs for improved performance.

Once we implemented these services, we had to string them together into what we call a Model Processing Pipeline. This pipeline is a chain of the services described above that takes in a 3D file at the start and outputs a fully priced, printable, rendered 3D Model on Shapeways.com. We defined these pipelines in another service called the Director, which is effectively a directed acyclic graph of model processing services.

To ensure that our services remain available at all times, we needed another layer to manage traffic. So rather than pointing directly to the services themselves, these steps indicate ActiveMQ queues, which act as load balancers for a pool of services that can handle a pipeline step. Using ActiveMQ in this fashion allows us to run our services anywhere in our hybrid cloud, as well as to scale at the service level rather than the pipeline level. Need more mesh repair compute in Europe? Spin up more instances in either our data center or AWS and subscribe them to the queue. With this capability, we’re able to optimize our model processing compute power for both user experience and cost, providing a best-of-both-worlds experience for Shapeways and our customer base.

Secure real-time rendering

Once we’ve got a printable model, we have to actually display it to the user in 3D for their review. Our uploaders have a chance to perform a visual review of key geometry components to be sure that our repair process didn’t alter the model. To assist with this review, we provide visualizations to help users understand potential problem areas with their models, such as thin walls or unintentionally connected parts. These visualizations are rendered directly on the users own computer graphics card, ensuring fast and reliable performance as they review their files.

Visualizing the customer’s own model is easy enough; they own the model, so they can render it on their system. But in addition to the online 3D printing service, Shapeways also provides a marketplace for our uploaders to open a shop and sell prints of their models. Our customers purchasing from our uploaders want to see a three-dimensional view of the models that they’re thinking about purchasing.

Here’s where the problem occurs—the industry-standard visualizations rendered on the consumers computer require us to transmit the entirety of the model file data to that users video card via WebGL. Bad actors can easily lift this 3D file from their own graphics cards, thereby stealing the model from the original uploader without paying for it, a massive violation of their IP rights. Shapeways takes the IP rights of all of our customers extremely seriously, so even the possibility of this edge case was deemed too risky to let stand. Therefore, we decided to build our own IP-safe 3D viewer to allow customers to view parts in 3D.

Enter ShapeJS. ShapeJS is a JavaScript-based tool we created to generate and display 3D geometry in real-time on the user’s browser. We created ShapeJS as a research project—could we create a web-based, voxel-backed, IP-safe, 3D design interface for developers as opposed to for those with background in 3D modeling? The back end of ShapeJS is built entirely in CUDA and runs directly on a server GPU for high-performance rendering.

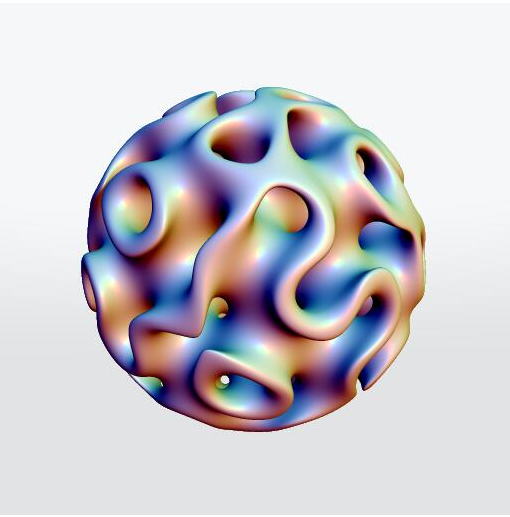

ShapeJS is a parametric design tool, which means that you describe the geometry you want to create in code, and the tool converts this into printable 3D geometry. For example, here’s a simple ShapeJS function to create a gyroid extruded through a sphere.

function main(args) {

var radius=25*MM;

var sphere=new Sphere(radius);

var gyroid=new VolumePatterns.Gyroid(args.period*MM,args.thickness*MM);

var intersect=new Intersection();

intersect.setBlend(2*MM);

intersect.add(sphere);

intersect.add(gyroid);

var s=26*MM;

return new Scene(intersect,new Bounds(-s,s,-s,s,-s,s));

}Let’s take it a few lines at a time.

var radius=25*MM;

var sphere=new Sphere(radius);

var gyroid=new VolumePatterns.Gyroid(args.period*MM,args.thickness*MM);These first three lines define two pieces of geometry: a sphere of radius 25mm and a gyroid with period and thickness defined by user-provided arguments.

var intersect=new Intersection();

intersect.setBlend(2*MM);

intersect.add(sphere);

intersect.add(gyroid);These four lines create a boolean intersection, set a blending radius to define how sharply the objects intersect each other (think photoshop blur tool), and then add both our sphere and our gyroid to the intersection. This effectively creates the sphere, then removes from it the area defined by the gyroid.

var s=26*MM;

return new Scene(intersect,new Bounds(-s,s,-s,s,-s,s));These final two lines create a ShapeJS Scene, which describes the visual render that will be returned to the ShapeJS interpreter for display. This scene is 52 milimeters wide, and contains the intersection of the sphere and the gyroid right in the middle. Running this function in the ShapeJS IDE will result in a nice, posable gyroid. You can play around with this here. There are other features such as configuring the UX that you’ll see in the code, but I omitted them for brevity.

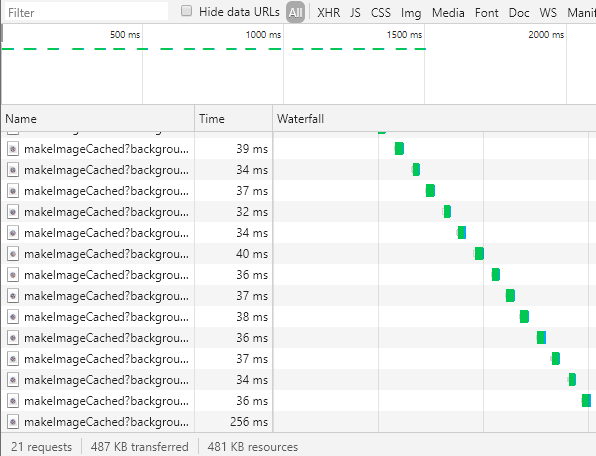

Now, let’s talk about IP safety. The crux of the issue is this: so long as we’re sending the actual 3D model file over the internet to the customer, we’re putting the model owner’s IP at risk. ShapeJS doesn’t work this way. Rather, what ShapeJS does is connect directly to a Shapeways-owned graphics card, where scripts interpret the model, and their results are returned to the user. The results, in this case, are 2D images of the portion of the 3D model that is visible in the scene. When the user interacts with the scene, the GPU renders the new “view” from the users perspective and streams it to their browser. This happens quite quickly and creates an animation that gives the end user the impression that they’re manipulating a 3D model in their browser. Here’s what those back end calls look like:

Managing the 3D printer infrastructure

Everything described up to this point is focused at the consumer-facing portion of Shapeways. However, we’re more than a website—Shapeways has two 3D printing facilities running around 80 machines in total, a supply chain network of over 70 production partners for overflow and special materials, and a global distribution footprint. We process over 10,000 individual (and often unique) parts through our system on a daily basis. In order to coordinate all of this activity, we’ve built an Enterprise Resource Planning (or ERP) tool, Inshape, from the ground-up, focused on the unique challenges presented by 3D printing.

ERPs are nothing new. Companies like Netsuite (now Oracle), SAP, Siemens, and more have been providing ERP software since the mid 90s. However, these solutions are aimed at traditional business—high-value individual customers purchasing large quantities of parts from a finite catalog of available offerings. For example, consider Ford Motor Company. They’ve got a set number of vehicles, each with a set bill of materials. When they need replacement headlamps from their provider, they know exactly what they’re buying, how much it costs, and who to pay for it.

Compare this to Shapeways: we have a large number of retail (implicity low-value, when compared to enterprises) customers, purchasing small quantities from a theoretically infinite catalogue of available offerings (something like 50% of what’s ordered on Shapeways on any given day is being ordered for the very first time). The available offerings just didn’t fit with our business needs. So if you can’t buy them, build them.

Inshape is a web-based ERP, designed with the goal of shepherding our customer orders from placement to shipment quickly, reliably, and at a high level of quality. Under the hood, Inshape is a collection of tools and services built to meet our goals, including up-to-the-second part tracking, workflow planning, quality monitoring, machine interfaces, and shipping provider integrations. I’ll speak specifically about two technically interesting features of Inshape: build planning and equipment monitoring.

When most people think of a 3D printer, the first image that pops into mind is something like a makerbot: a desktop printer that produces a single part at a time. At Shapeways, we’re using industrial 3D printers capable of producing up to 1000 parts at once. In order to use our machines as efficiently as possible, we need to get as many of our current backlog of parts into a printer as we safely can on every single build. This is what’s known in computer science as a Packing Problem. Where we differ from the norm is that we’re not packing known objects; we’re packing a unique set of parts that varies every single time we need to pack a job.

To solve this problem, we’ve built our own, in-house packing solution. We combine the knowledge we have about our customer lead times, specific geometries in our pipeline, known capabilities of our individual printers, and years of experience manufacturing parts into a service which autonomously and iteratively packs jobs for production. We’ve been able to almost double the industry standard of job density though this system, resulting in shorter lead times for our customers and more throughput for our factories.

Now, about those machines. As mentioned earlier, they’re not your standard desktop 3D printers. They’re expensive assets that have maintenance requirements, service contracts, and individuals designated to each of them who are responsible for keeping them up and running. These machines produce a ton of data about each individual job—how long did it run, how much material did it consume, what percentage of each individual layer of the build was exposed to the sintering laser... the list goes on. On most of our printers, however, this data was never designed to leave the machine. This makes it almost impossible to aggregate this data with the overall production data that we have in our system. Boo!

The good news is that, by hook or by crook, we’re able to retrieve this data from most of our machines. Whether it’s by API client (the best case) to remotely monitoring log files and inferring actions (not the best case), we have designed a system to collect data from these machines and aggregate it in a primary data center location. The system is really neat—we’ve built a service that’s capable of being deployed as a primary (in the data center, as an authoritative source) or buffer (in the factories, directly communicating to machines) configuration. This split enables us to have real-time access to machine data in our factories for real-time decisions, while ensuring eventual consistency in our data centers for more historical reports like efficiency or uptime. As we continue to invest in understanding our manufacturing equipment, we see a direct correlation in our efficiency and speed of manufacturing.

As you can see, software is a critical part of the 3D printing world. Whether it’s preparing a file for production, creating compelling visuals for merchandising and sales, or facilitating the production, fulfillment, and quality of the end print, if you don’t have the right software, you don’t have much. I hope this peek behind the curtain has been helpful. Thanks for reading!

The Stack Overflow blog is committed to publishing interesting articles by developers, for developers. From time to time that means working with companies that are also clients of Stack Overflow’s through our advertising, talent, or teams business. When we publish work from clients, we’ll identify it as Partner Content with tags and by including this disclaimer at the bottom.