[Ed. note: While we take some time to rest up over the holidays and prepare for next year, we are re-publishing our top ten posts for the year. Please enjoy our favorite work this year and we’ll see you in 2022.]

Famed MIT professor Hal Abelson said: "Programs must be written for people to read and only incidentally for machines to execute." While he may have purposely understated the importance of running code, he is spot on that programs have two very different audiences. Compilers and interpreters ignore comments and find all syntactically correct programs equally easy to understand. Human readers are very different. We find some programs harder to understand than others, and we look to comments to help us make sense of them.

While there are many resources to help programmers write better code—such as books and static analyzers—there are few for writing better comments. While it's easy to measure the quantity of comments in a program, it's hard to measure the quality, and the two are not necessarily correlated. A bad comment is worse than no comment at all. As Peter Vogel has written:

- Writing and then maintaining comments is an expense.

- Your compiler doesn't check your comments so there is no way to determine that comments are correct.

- You are, on the other hand, guaranteed that the computer is doing exactly what your code is telling it to.

While all of these points are true, it would be a mistake to go to the other extreme and never write comments. Here are some rules to help you achieve a happy medium:

Rule 1: Comments should not duplicate the code.

Rule 2: Good comments do not excuse unclear code.

Rule 3: If you can't write a clear comment, there may be a problem with the code.

Rule 4: Comments should dispel confusion, not cause it.

Rule 5: Explain unidiomatic code in comments.

Rule 6: Provide links to the original source of copied code.

Rule 7: Include links to external references where they will be most helpful.

Rule 8: Add comments when fixing bugs.

Rule 9: Use comments to mark incomplete implementations.

The rest of this article explains each of these rules, providing examples and explaining how and when to apply them.

Rule 1: Comments should not duplicate the code

Many junior programmers write too many comments because they were trained to do so by their introductory instructors. I've seen students in upper-division computer science classes add a comment to each closed brace to indicate what block is ending:

if (x > 3) {

…

} // ifI've also heard of instructors requiring students to comment every line of code. While this may be a reasonable policy for extreme beginners, such comments are like training wheels and should be removed when bicycling with the big kids.

Comments that add no information have negative value because they:

- add visual clutter

- take time to write and read

- can become out-of-date

The canonical bad example is:

i = i + 1; // Add one to iIt adds no information whatsoever and incurs a maintenance cost.

Policies requiring comments for every line of code have been rightly ridiculed on Reddit:

// create a for loop // <-- comment

for // start for loop

( // round bracket

// newline

int // type for declaration

i // name for declaration

= // assignment operator for declaration

0 // start value for i

Rule 2: Good comments do not excuse unclear code

Another misuse of comments is to provide information that should have been in the code. A simple example is when someone names a variable with a single letter and then adds a comment describing its purpose:

private static Node getBestChildNode(Node node) {

Node n; // best child node candidate

for (Node node: node.getChildren()) {

// update n if the current state is better

if (n == null || utility(node) > utility(n)) {

n = node;

}

}

return n;

} The need for comments could be eliminated with better variable naming:

private static Node getBestChildNode(Node node) {

Node bestNode;

for (Node currentNode: node.getChildren()) {

if (bestNode == null || utility(currentNode) > utility(bestNode)) {

bestNode = currentNode;

}

}

return bestNode;

} As Kernighan and Plauger wrote in The Elements of Programming Style, "Don't comment bad code — rewrite it."

Rule 3: If you can't write a clear comment, there may be a problem with the code

The most infamous comment in the Unix source code is "You are not expected to understand this," which appeared before some hairy context-switching code. Dennis Ritchie later explained that it was intended "in the spirit of 'This won't be on the exam,' rather than as an impudent challenge." Unfortunately, it turned out that he and co-author Ken Thompson didn't understand it themselves and later had to rewrite it.

This brings to mind Kernighan's Law:

Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place. Therefore, if you write the code as cleverly as possible, you are, by definition, not smart enough to debug it.

Warning readers away from your code is like turning on your car's hazard lights: an admission that you're doing something you know is illegal. Instead, rewrite the code to something you understand well enough to explain or, better yet, that is straightforward.

Rule 4: Comments should dispel confusion, not cause it

No discussion of bad comments would be complete without this story from Steven Levy's Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution:

[Peter Samson] was particularly obscure in refusing to add comments to his source code explaining what he was doing at a given time. One well-distributed program Samson wrote went on for hundreds of assembly-language instructions, with only one comment beside an instruction that contained the number 1750. The comment was RIPJSB, and people racked their brains about its meaning until someone figured out that 1750 was the year Bach died, and that Samson had written an abbreviation for Rest In Peace Johann Sebastian Bach.

While I appreciate a good hack as much as the next person, this is not exemplary. If your comment causes confusion instead of dispelling it, remove it.

Rule 5: Explain unidiomatic code in comments

It's a good idea to comment code that someone else might consider unneeded or redundant, such as this code from App Inventor (the source of all of my positive examples):

final Object value = (new JSONTokener(jsonString)).nextValue();

// Note that JSONTokener.nextValue() may return

// a value equals() to null.

if (value == null || value.equals(null)) {

return null;

}

Without the comment, someone might "simplify" the code or view it as a mysterious but essential incantation. Save future readers time and anxiety by writing down why the code is needed.

A judgment call needs to be made as to whether code requires explanation. When learning Kotlin, I encountered code in an Android tutorial of the form:

if (b == true)I immediately wondered whether it could be replaced with:

if (b)as one would do in Java. After a little research, I learned that nullable Boolean variables are explicitly compared to true in order to avoid an ugly null check:

if (b != null && b)I recommend not including comments for common idioms unless writing a tutorial specifically for novices.

Rule 6: Provide links to the original source of copied code

If you're like most programmers, you sometimes use code that you find online. Including a reference to the source enables future readers to get the full context, such as:

- what problem was being solved

- who provided the code

- why the solution is recommended

- what commenters thought of it

- whether it still works

- how it can be improved

For example, consider this comment:

/** Converts a Drawable to Bitmap. via https://stackoverflow.com/a/46018816/2219998. */Following the link to the answer reveals:

- The author of the code is Tomáš Procházka, who is in the top 3% on Stack Overflow.

- One commenter provides an optimization, already incorporated into the repo.

- Another commenter suggests a way to avoid an edge case.

Contrast it with this comment (slightly altered to protect the guilty):

// Magical formula taken from a stackoverflow post, reputedly related to

// human vision perception.

return (int) (0.3 * red + 0.59 * green + 0.11 * blue);Anyone looking to understand this code is going to have to search for the formula. Pasting in the URL is much quicker than later finding the reference.

Some programmers may be reluctant to indicate that they did not write code themselves, but reusing code can be a smart move, saving time and giving you the benefit of more eyeballs. Of course, you should never paste in code that you don't understand.

People copy a lot of code from Stack Overflow questions and answers. That code falls under Creative Commons licenses requiring attribution. A reference comment satisfies that requirement.

Similarly, you should reference tutorials that were helpful, so they can be found again and as thanks to their author:

// Many thanks to Chris Veness at http://www.movable-type.co.uk/scripts/latlong.html

// for a great reference and examples.Rule 7: Include links to external references where they will be most helpful

Of course, not all references are to Stack Overflow. Consider:

// http://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc4180 suggests that CSV lines

// should be terminated by CRLF, hence the \r\n.

csvStringBuilder.append("\r\n");

Links to standards and other documentation can help readers understand the problem your code is solving. While this information may be somewhere in a design document, a well-placed comment gives readers the pointer when and where it is most needed. In this case, following the link indicates that RFC 4180 has been updated by RFC 7111—useful information.

Rule 8: Add comments when fixing bugs

Comments should be added not just when initially writing code but also when modifying it, especially fixing bugs. Consider this comment:

// NOTE: At least in Firefox 2, if the user drags outside of the browser window,

// mouse-move (and even mouse-down) events will not be received until

// the user drags back inside the window. A workaround for this issue

// exists in the implementation for onMouseLeave().

@Override

public void onMouseMove(Widget sender, int x, int y) { .. }

Not only does the comment help the reader understand the code in the current and referenced methods, it is helpful for determining whether the code is still needed and how to test it.

It can also be helpful to reference issue trackers:

// Use the name as the title if the properties did not include one (issue #1425)While git blame can be used to find the commit in which a line was added or modified, commit messages tend to be brief, and the most important change (e.g., fixing issue #1425) may not be part of the most recent commit (e.g., moving a method from one file to another).

Rule 9: Use comments to mark incomplete implementations

Sometimes it's necessary to check in code even though it has known limitations. While it can be tempting not to share known deficiencies in one's code, it is better to make these explicit, such as with a TODO comment:

// TODO(hal): We are making the decimal separator be a period,

// regardless of the locale of the phone. We need to think about

// how to allow comma as decimal separator, which will require

// updating number parsing and other places that transform numbers

// to strings, such as FormatAsDecimal

Using a standard format for such comments helps with measuring and addressing technical debt. Better yet, add an issue to your tracker, and reference the issue in your comment.

Conclusion

I hope the above examples have shown that comments don't excuse or fix bad code; they complement good code by providing a different type of information. As Stack Overflow co-founder Jeff Atwood has written, "Code Tells You How, Comments Tell You Why."

Following these rules should save you and your teammates time and frustration.

That said, I'm sure these rules aren't exhaustive and look forward to seeing suggested additions in (where else?) the comments.

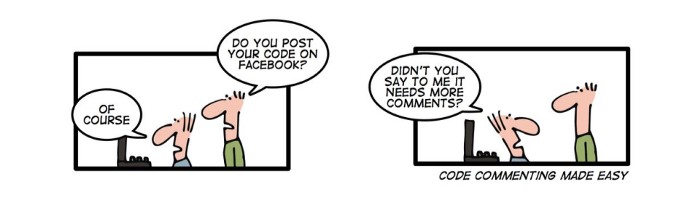

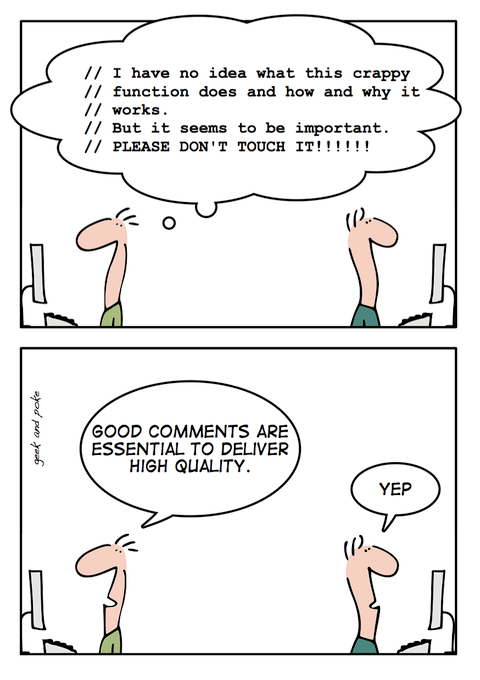

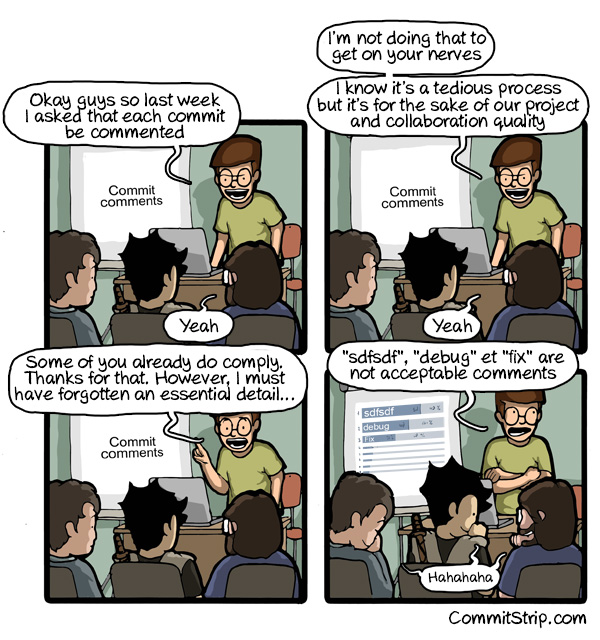

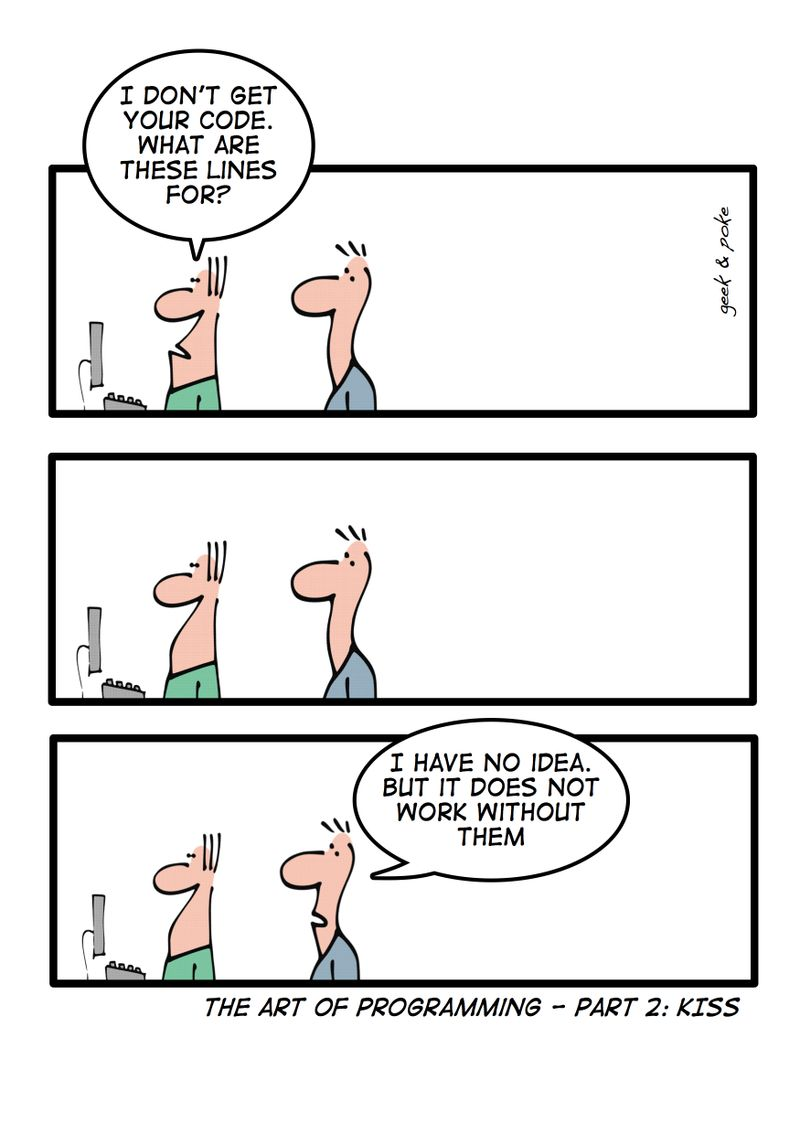

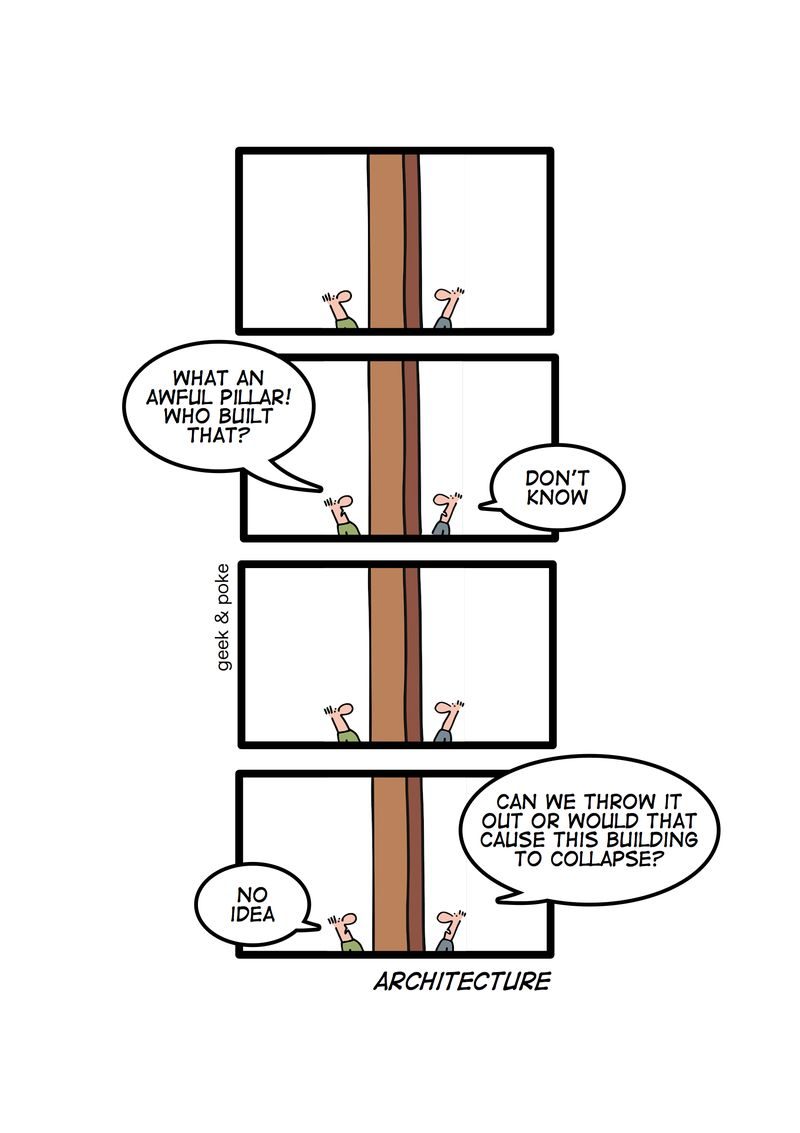

Memes and cartoons

For your consideration...

Source: https://www.reddit.com/r/ProgrammerHumor/comments/8w54mx/code_comments_be_like/

Source: https://www.reddit.com/r/ProgrammerHumor/comments/bz35nh/whats_a_comment/

Source: https://geekandpoke.typepad.com/geekandpoke/2011/06/code-commenting-made-easy.html

https://geekandpoke.typepad.com/geekandpoke/2008/07/good-comments.html

Source: https://www.commitstrip.com/en/2016/09/01/keep-it-simple-stupid/?

https://www.commitstrip.com/en/2013/07/22/commentaire-de-commit/?

https://geekandpoke.typepad.com/geekandpoke/2009/07/

https://geekandpoke.typepad.com/geekandpoke/2010/11/architecture.html