[Ed. note: While we take some time to rest up over the holidays and prepare for next year, we are re-publishing our top ten posts for the year. Please enjoy our favorite work this year and we’ll see you in 2023.]

Many apps today are actually a front-end for a series of API calls. APIs are necessary to proper functioning of such applications, but if you don’t protect them, bad actors can exfiltrate data, DDoS your servers, or otherwise abuse them.

OAuth is one of many solutions you can use to protect your APIs and other resources. It allows users to securely delegate access to resources without sharing their original credentials. OAuth2 (the version of OAuth that this article will cover) has been around since 2012 as a standard and is built on lessons from other, earlier standards, including OAuth1 and SAML.

Being a standard, OAuth benefits from many smart people working together in the open. As a user of this standard, you gain all their hard work without having to hire them! This work includes security analysis, where the group constantly considers different attack vectors and weaknesses in the protocol and ameliorates them. The members of the group also work to support weird edge cases in scale, user interfaces, and network connectivity. If you have a typical auth use case, the OAuth standard almost certainly will work for you.

If you need core functionality, you should be covered by almost any OAuth server. But if you need specialized functionality, even if it is part of a standard, carefully review the documentation of any solution you are considering.

While I’ll dive further into how you actually use OAuth to protect an API in your system below, including code examples, I won’t cover certain topics in this article. Some of the topics that will be omitted include:

- Every single OAuth related specification. There are a lot of them!

- All the edge cases OAuth and related standards can address.

- How to use OAuth to access a third party API such as Google. This is a related use case, but different enough that it doesn’t make sense to cover it.

When you are done with this article, you’ll know more about why you might choose OAuth, when to use it, and some alternatives.

Why use OAuth to protect your APIs?

When you are using OAuth, you outsource user authentication and authorization to a central identity provider (IdP). Users sign in to the IdP and are granted time-bound permissions in the form of an access token. This token is presented to other applications, APIs, and services.

Using such a centralized service has a number of advantages:

- One system holding user PII can be locked down and protected more easily than many systems.

- Just as a database is focused on retaining data with certain guarantees, an IdP can focus on login functionality and provide a well understood interface.

- Because an IdP is the place where authorization and authentication decisions are performed, it becomes a single central location for analyzing, enabling, and disabling access to systems.

- When all users authenticate at the IdP, you can easily add functionality, such as federation to other identity sources or security measures like multi-factor authentication. All applications, APIs and services which accept tokens from the IdP benefit from additional functionality without any change to their code.

OAuth, having been around for over a decade, is ubiquitous. There are OAuth clients in almost every modern programming language, and even some less modern ones such as COBOL. This ubiquity means that when you are working with an OAuth server, you can leverage libraries to perform the integration quickly.

It has been extended multiple times for specialized use cases (called profiles) and new authorization flows (called grants). The standards body behind OAuth, the OAuth IETF working group, offers best practices for newer technologies like mobile applications or IoT devices.

Below I will discuss the core standards you should know, but be aware that not every IdP implements every standard within the OAuth umbrella. Examples of standards that may not be implemented include:

- The device grant, which lets you perform an OAuth flow for a device with limited user input options.

- Dynamic client registration, which allows clients to register with an IdP in an automated fashion, without human or out-of-band intervention.

- MTLS, which allows mutual X.509 certificates to be used for authentication and to bind tokens to specific clients.

A sampling of specifications

OAuth was built to be extended. Unlike earlier auth related specifications like SAML, which were monolithic, large and difficult to implement, OAuth is composable and extendable. Even the core specification was delivered in two RFCs, RFC 6749 (which covers the flows) and RFC 6750 (which details the token).

Below are brief overviews of the core standards, as well as some that are useful in particular circumstances. You’ll also learn about standards that are not yet codified, but are worth keeping an eye on. If you plan on implementing any of these, it’s always a good idea to dive into the RFC texts themselves.

Core OAuth standards

These are the core OAuth standards, though not every implementation has to use every one of them.

- RFC 6749 and RFC 6750: As mentioned above, these comprise the beating heart of OAuth. The former covers the main authorization flows, called grants. The latter covers how the access token, the end product of a grant, should be used when it is a bearer token (most of the time, it will be a bearer token). A bearer token is not bound to a particular client. I like to think of a bearer token like a car key: anyone who holds the key can start the car. In the same way, anyone who holds a bearer token can gain access to resources protected by it.

- RFC 7519 documents a common token format, JSON Web Tokens or JWTs. JWTs are JSON objects which contain claims (which is fancy for “data, possibly with a standardized meaning”) about an entity for whom the token was issued. They are typically cryptographically signed, which allows them to be verified and trusted. Sibling standards further define JWTs and related functionality: RFC 7515, RFC 7516, RFC 7517, RFC 7518 and RFC 7520. RFC 7517 is especially useful as it covers publishing public keys, which allows asymmetric signing algorithms such as RSA to be used to sign a JWT.

- OpenID Connect (OIDC) is an extension of OAuth (called a profile) that allows access to authentication information. Although OAuth can and is used without OIDC, they are often implemented together.

- RFC 7662 documents introspection. This process validates an access token by communicating with the OAuth server that created it. Using introspection is an alternative to JWTs and other self-contained token formats.

- RFC 7636 outlines PKCE (pronounced ‘pixie’) and is an example of how standards address security issues. PKCE protects clients incapable of holding secrets, such as browser or mobile applications, from an entire class of attacks. PKCE is recommended for all clients using the Authorization Code grant.

- The evolving OAuth2.0 Security best current practices (BCP) document discusses security threats and extends the 2013 OAuth threat model standard, RFC 6819, which is almost a decade old.

Next, let’s look at some interesting standards which might not be applicable in every situation.

Specialized OAuth standards

Since OAuth is extensible, some optional functionality may be very important to you, and some may not. There’s no central repository showing which IdPs support which standards, so check technical documentation to ensure you get the implementation and functionality you need.

Some standards that fall into this category include:

- RFC 8252 discusses OAuth grants and mobile applications. Since mobile applications cannot maintain secrets and each application has a high level of control over the user input, there are certain additional steps you must take to ensure security. This is especially important if the client and the IdP are not controlled by the same organization.

- RFC 7591, dynamic client registration, allows clients to register themselves. In core OAuth, client registration occurs rarely and is typically done in a manual manner. With this RFC, clients can discover everything they need to register themselves. This is useful when you want to have many unique clients.

- RFC 8628 creates an additional grant, the device grant, designed specifically for clients that have limited user input options, such as televisions or other appliances. With this grant, people may log in using a secondary input device, such as a computer or phone, and still have the original client receive the access token.

- RFC 9068 covers how to specify JWT access tokens in a standard format, allowing different IdPs and resource servers to interoperate.

- DPoP/MTLS addresses an issue left unresolved with the core token RFC, 6750, because of implementation complexity. These documents (the former of which is a draft, not a full-fledged RFC) outline how to bind a token to a particular client. Each of these uses a different mechanism, but if the idea of a bearer token being stolen and used by a malicious actor is unacceptable to you or your security team, using these can help.

OAuth continues to evolve and there are two main efforts to improve it. Let’s discuss these efforts in the next section.

OAuth’s future

While there are plenty of incremental improvements being discussed in various standards bodies, the two main efforts to improve the core of OAuth are OAuth 2.1 and GNAP.

OAuth 2.1 is currently under active development. This specification consolidates best practices around security and usability which have been added to OAuth over the years since it was released. The authors have explicitly ruled out any breaking changes or radical modifications.

GNAP, on the other hand, is a reimagination of the OAuth protocol, in the same way that OAuth2 was a reimagining of earlier protocols. This early draft includes breaking changes such as introducing new software actors and changing the core communication format from form parameters to JSON.

Whew, that was a lot. Hopefully this gives you an idea of the breadth and width of the OAuth landscape as well as the kinds of problems you can solve using it.

Next, let’s dig into some details.

Which grant should I use?

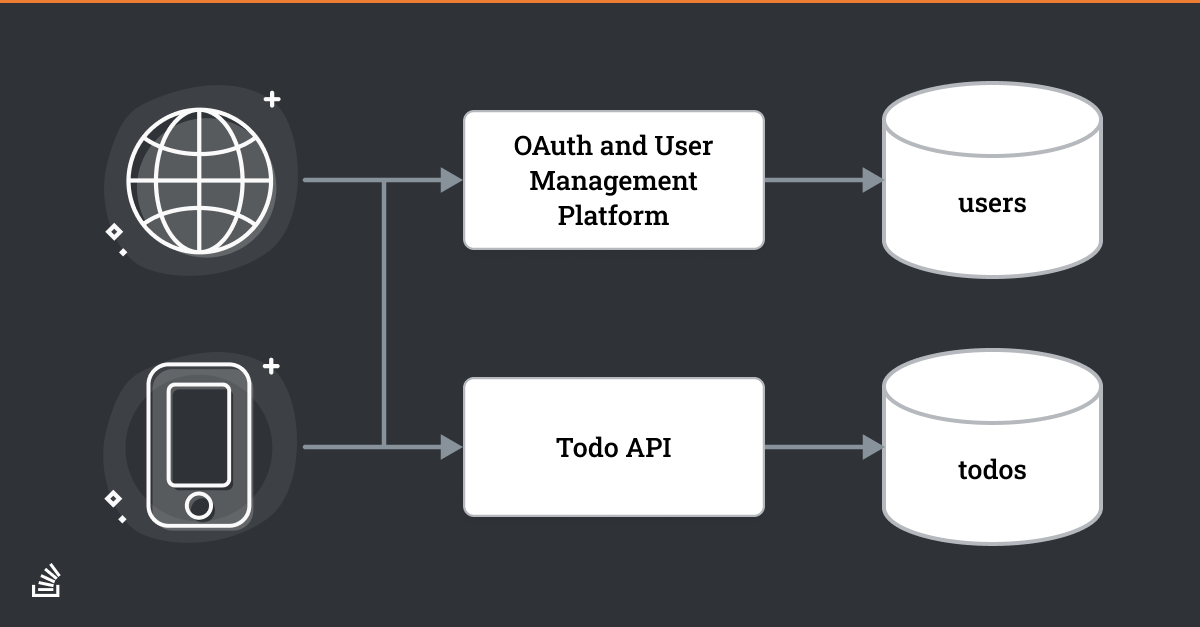

Consider a simple application, diagrammed above, which allows users to manage todos. Clients like a web browser or mobile app will access two different components: an OAuth platform to authenticate users and a Todo API to add, update, or delete todos.

An OAuth grant is a specific flow that results in an access token. Per the specification, a token is an opaque string without any structure. However, OAuth servers can choose their token format, and many use JSON Web Tokens, which do have internal structure. Some parts of the grant, such as error messages or expected parameters, are well defined. Others, such as the actual authentication process, are left as implementation details.

A grant authenticates the user or other entity, assembles appropriate permissions based on user roles, groups, and requested scopes, gathers the authorization data, and encapsulates those permissions from the authorization server in the form of an access token. Here’s an example of a token: mF_9.B5f-4.1JqM.

The token is often, but not always, sent to the client for later presentation to the resource server. In the diagram above, the mobile apps and browser on the left will be going through an OAuth grant in order to gain access to the Todo API.

In this context, which grant should you choose to send your users through? The core RFC, RFC 6749, defines a number of grants. It can be confusing to determine which is the best fit for your use case.

For most developers, there are really only a few questions to ask:

- Is there a human being involved?

- How long will the client need access to the protected resource?

Let's tackle each question.

Is there a human being involved?

Whenever a user is involved, the best grant to use is the Authorization Code grant. This grant will be discussed in more detail below. Using this offers architectural flexibility around the final location of the access token as well as a better security profile. In general, you should pair the Authorization Code grant with PKCE.

In the todo application outlined in the diagram above, a human being is making the initial request to display todos in their application, so the Authorization Code grant should be used.

But let's consider a different situation.

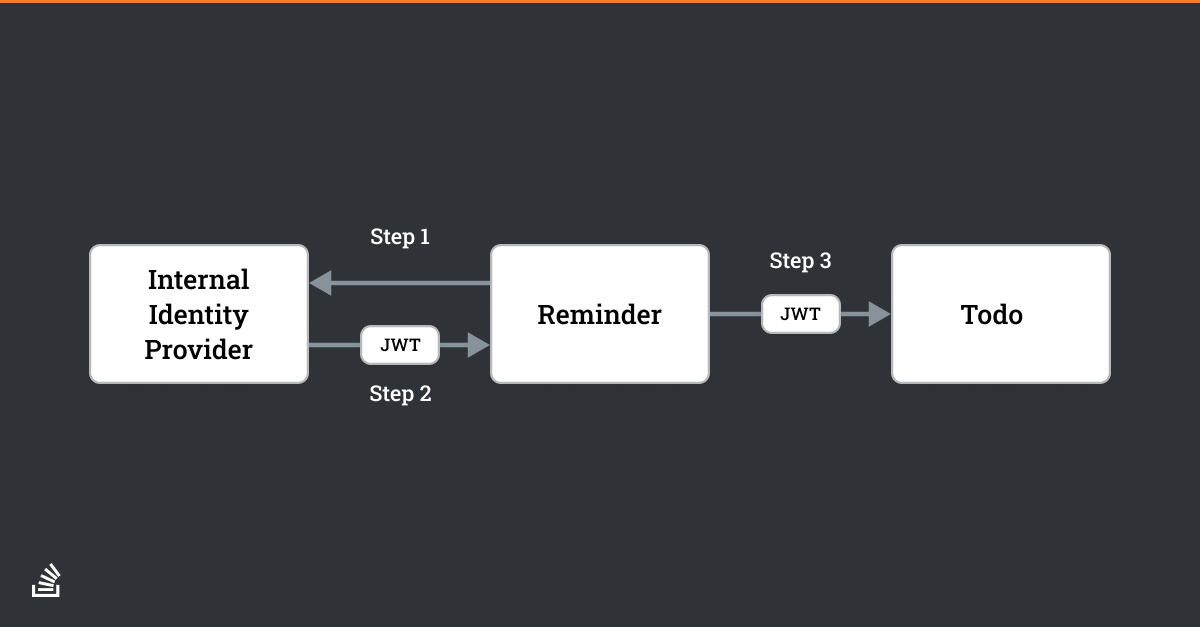

Suppose we extend the application with new functionality to remind our users of deadlines associated with their todos.

In that case, we need a reminder service which would run every day, see which todos were due, and send a reminder email. This service would still need to authenticate because we wouldn’t want anyone to be able to access our todos. But there is no user kicking off the request—perhaps its only a cron job.

That flow of permissions might look a little something like this:

When there is no human being starting the request, the correct grant to use is the Client Credentials grant. This grant should be used whenever you have service to service communication and want to leverage the client library support, centralized authentication, and security infrastructure of an authorization server.

How long will the client need access to the protected resource?

In general, access tokens are good for a short period of time (seconds to minutes). If the client can gain access to the resources it needs in that time, then all is well and good. However, sometimes the client needs access for the longer term. When the access token expires, the client can either ask the user to re-authenticate or it can use the Refresh grant.

This grant allows a client to transparently re-request a token with the same permissions without forcing the user to re-authenticate.

What about the other grants?

The other grants, such as the Device grant or the Resource Owner Password grant, should be used only when the use case calls for their specific functionality.

In general, use the Authorization Code grant if there is a human being involved and the Client Credentials grant if you are performing server to server communication.

Alternatives to OAuth

OAuth isn’t the only option to protect your API. The main alternative is API keys. They are a good solution in some situations and they are simple to understand. However, compared to OAuth, they do have some deficiencies.

API keys are relatively static. While you can and should rotate API keys, you have to build the infrastructure to do this yourself. API keys are not time-bound unless you also build this into your system.

API keys are “secrets” and should be managed as such. Just like the OAuth client secret, API keys are privileged data, which means you can’t, for example, store them safely in JavaScript. Therefore, they limit your architectural flexibility.

There also is no encoded information in an API key, unlike tokens, which may have encoded information, especially if an access token is a JWT. This richer data format can include useful business-specific information such as a todo app subscription level. It also allows for authorization to be performed without requiring “phoning home” to the the OAuth server which created the token.

Conclusion

In this article, you learned about why OAuth is a good choice to protect access to your APIs, more about its component standards, and options for using OAuth grants to protect resources. You also learned about alternatives to using OAuth such as API keys.

While OAuth can be complex, it handles a large number of use cases. You separate out the concern of authentication to a specialized component, while using a standardized temporary credential (the token) in the rest of your system. In addition, by using OAuth, you leverage standards and expertise from all over the world.

In the next article in this two part series, we'll look at how the Authorization Code grant works in step by step detail with code, as well as how you should validate a token.