[Ed. note: While we take some time to rest up over the holidays and prepare for next year, we are re-publishing our top ten posts for the year. Please enjoy our favorite work this year and we’ll see you in 2024.]

I recently stumbled upon “Software disenchantment,” a post by Nikita Prokopov. It called to mind Maciej Cegłowski’s post “The Website Obesity Crisis” and several others in the same vein. Among people who write about software development, there’s a growing consensus that our apps are getting larger, slower, and more broken, in an age when hardware should enable us to write apps that are faster, smaller, and more robust than ever. DOOM, which came out in 1996, can run on a pregnancy test and a hundred other unexpected devices; meanwhile, chat apps in 2022 use half a gigabyte of RAM (or more) while running in the background and sometimes lock up completely, even on high-end hardware.

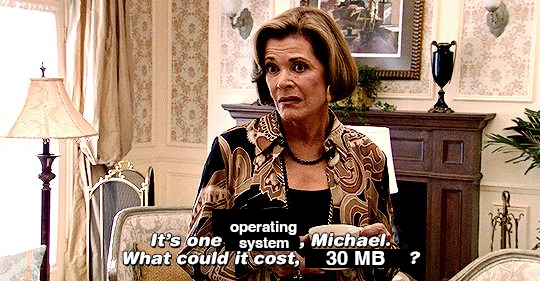

The aforementioned posts on this subject come across as about 80% fair and reasonable criticism, 20% out-of-touch grumbling. Or in other words:

Most developers know better than to say things like “it’s a smartphone OS, how hard can it be?” or “my spreadsheet app in the 90s was 10 kilobytes, how come Factorio is a full gigabyte?” If you weren’t there when it was built, you can’t reliably estimate all the hard knocks and complexity that went into it.

But that doesn’t mean there’s no room for objective criticism. Apps are slower than they used to be. And exponentially larger without a corresponding increase in value. At the very least, there are optimization opportunities in almost any modern app. We could make them faster, probably by orders of magnitude. We could remove code. We could write tiny, purpose-built libraries. We could find new ways to compress assets.

Why don’t we?

Prokopov’s answer is “software engineers aren’t taking pride in their work.” There’s some truth to that. But I strongly believe it’s the natural human state to work hard and make excellent things, and we only fail to do so when something repeatedly stops us. So instead of relying on the myth of laziness to explain slow and buggy software, we should be asking “what widespread forces and incentives are creating an environment where it’s hard for software engineers to do their best work?”

I have a few answers to that.

Speed is a feature, reliability is nothing

Software is envisioned by engineers as networks of interacting components, inputs, and outputs. This model is both accurate and useful. However, it’s not the way software is packaged, marketed, or sold. To businesspeople and customers, software is a list of features.

Take an inventory management app as an example. Its marketing materials will consist of several high-res stock photos, a bold color palette, and statements like the following:

- Tracks inventory across multiple warehouses

- Integrates with Delivery Pro, Supply Chain Plus, and Super Point-of-Sale systems

- Weekly and monthly reporting at multiple levels

- Fine-grained access and security controls

- Instant updates across all terminals

- Runs on Windows, MacOS, and Linux

These are falsifiable statements; either the software does these things or it does not. They can all be proven in a one-hour product demo. And only one deals with speed. The software may in fact be very slow, taking several seconds to respond to a button click, without making the “instant updates” claim a lie.

We can all agree that speed affects a user’s entire experience of an app. It’s an important marker of quality. But it’s difficult to sell. If you spend your time optimizing a core process while your competitor develops a new type of report, you’ll lose eight of your next ten sales over it. If you poll your existing customers about what you should work on next, they’re going to ask for features, not speed—unless the software is so slow it borders on unusable. And god forbid any red-blooded board of directors would allow the company to take a six-month detour from its product roadmap to work on technical debt. The pressure is always on us to build features, features, features.

Programmers want to write fast apps. But the market doesn’t care.

You may notice reliability isn’t on the list at all. How exactly would you say that? “Bug-free?” There’s no way to ensure that, let alone prove it in a product demo. “90% unit test coverage and a full suite of integration tests?” Nobody knows what that means and if you explained it to them, they’d be bored. There’s no way to express reliability in a way customers will both believe and care about. The Agile age has taught them that bugs will inevitably exist and you’ll fix them on an ongoing basis. And since there’s no comprehensive way to measure defects in software (surely if we knew about them, we would have already fixed them?) it’s not a feature that can be compared between products. We can invest time to test, refactor, and improve, but it’s entirely possible no one will notice.

Programmers want to write bug-free apps. But the market doesn’t care.

Disk usage isn’t on the list either, though occasionally it appears in small, low-contrast print below a “Download” button. And of everything here, this one is perhaps least connected with competitiveness or quality in customers’ minds. When was the last time you blamed a developer (as opposed to yourself or your computer) when you ran out of disk space? Or chose between two video games based on download size? Probably never. You can find people who complain about the size of the latest Call of Duty, but the sequels still make a billion dollars the week they come out.

Shrinking an executable or output bundle is thankless work. And it’s often highly technical work, requiring an understanding of not just the app one is building but the hundreds of lower-level libraries it depends on. Furthermore, it’s actively discouraged (“don’t reinvent the wheel”), partially because it’s a minefield. You may not know what a line of code is for, but that doesn’t mean it’s useless. Maybe it’s the difference between a working app and a broken one for the 0.01% of your customers that use Ubuntu on a smartphone. Maybe it’s the one thing keeping the app from crashing to a halt every four years on Leap Day. Even the smallest utility function eventually develops into an artifact of non-obvious institutional knowledge. It’s just not worth messing with.

Some programmers want to write smaller apps. But the benefits aren’t there for the market or for us.

Consumer software is undervalued

It’s not hard to distribute an app. That’s more or less what the Internet is for. But selling an app is like pulling teeth. The same general public who will pay $15 for a sandwich or a movie ticket—and then shrug and move on if they didn’t like it—are overcome by existential doubt if an app they’re interested in costs one (1) dollar. There are only two demographics that are willing to pay for good software: corporations and video gamers. We’ve somehow blundered our way into a world where everyone else expects software to be free.

This expectation has been devastating to the quality of consumer apps. Building an app costs anywhere from 50,000 to half a million dollars. If you can’t get people to pay on the way in, you have to recoup costs some other way. And herein are the biggest causes of bloat and slowness in both web and native applications: user tracking, ads, marketing funnels, affiliate sales, subscription paywalls, counter-counter-measures for all the above, and a hundred even-less-reputable revenue streams. These things are frequently attributed to greed, but more often they’re a result of desperation. Some of the most popular websites on the Internet are just barely scraping by.

It’s hard to overstate the waste and inefficiency of a system like this. You publish a unique, high-quality app for what you believe to be a fair price. It sits at zero downloads, day after day. You rebuild it on a free trial/subscription model. It gets a few hundred downloads but only a handful of users convert to a paid plan, not nearly enough to cover your costs. You put ads in the free version, even though it breaks your UI designer’s heart. You find out that ad views pay out in fractions of a cent. You put in more ads. Users (who, bafflingly, are still using the app for free) complain that there are too many ads. You swap some ads for in-app purchases. Users complain about those, too. You add call-to-action modals to encourage users to pay for the ad-free experience. You find out most of them would sooner delete the app. You add analytics and telemetry so you can figure out how to increase retention. You discover that “retention” and “addiction” might as well be synonyms. The cycle goes on, and before long you no longer have an app; you have a joyless revenue machine that exploits your users’ attention and privacy at every turn. And you’re still not making very much money.

We could avoid all of this if people were willing to pay for apps. But they’re not. So apps are huge and slow and broken instead.

Developers don’t realize the power they have

Lest I be accused of blaming everyone but myself, let’s examine the role of software developers. There has to be something we can do better.

Even in a recession, developers have an extraordinary amount of leverage. We can insist on working with (or not working with) specific technologies. We can hold out for high salaries, benefits, and equity. We can change the culture and work environment of an entire company by exercising even the slightest amount of solidarity. Good programmers are hard to come by. Everyone knows it, and we know they know it.

That’s our power, and we can do more with it.

We should set aside time in every sprint to resolve technical debt. We should procrastinate feature work now and then when there’s an especially promising opportunity to optimize and improve our code. We should persuade our employers to sponsor open-source projects. We should create the expectation that we won’t always be working on the product roadmap; our code and our industry expect more of us.

Most of the time there won’t be any negative consequences. We’re not asking too much. Every other industry has professional standards and requirements that transcend any one job description. Why do we so often act like software development doesn’t?

The only caveat is that the incentives aren’t in our favor. It’s an uphill battle. Some managers won’t be comfortable with us spending time on things they don’t understand. Some salespeople will worry that our software isn’t competitive. Investors may threaten to outsource our work to more pliable developers. It will be a while before customer attitudes and market forces shift. But if changing the state of modern software is a worthy goal, then it’s worth the effort.

Will it get better?

It’s hard to be optimistic about the future of software. Programmers were allowed to build tiny, highly-optimized apps in the 90s because there was no other choice. Their customers had 32 megabytes of RAM and a 200 megahertz single-core processor. If an app wasn’t as lean as possible, it wouldn’t run at all. Today, a two-year-old base-model Macbook Air has 250 times as much memory (not to mention faster memory) and a quad-core processor with several times the speed on any one core. You can get away with a lot more now. And we do. We ship apps that are 90% dead weight. We don’t optimize until someone complains. We package a full web browser installation with apps for sending messages, taking notes, even writing our own code (I’m using one right now).

The last two decades have been dedicated to making software development faster, easier, and more foolproof. And admittedly, we’re creating apps faster than ever, with more features than ever, using less experienced developers than ever. It’s not hard to see the appeal from a business perspective. But we’re paying the price—and so are our customers, the power grid, and the planet.

Things won’t change overnight, probably not even in the next five years. But there are reasons to be hopeful.

The latest wave of web programming languages and technologies (like WebAssembly, ESBuild, SWC, Bun, and Yew) is enabling new levels of speed and reliability, both at compile-time and runtime. Rust, noted for delivering the performance of C and the developer-friendliness of higher-level languages, is gaining popularity on web servers. Lightweight Electron alternatives like Tauri are poised to take over as the web developer’s cross-platform framework of choice. Tree-shaking is something we’ve come to expect from compilers and bundlers.

In terms of the market, several popular video games (like Dead Cells and The Binding of Isaac) have made their way to mobile platforms as paid downloads. There’s still a lot of work to be done, but this is promising headway towards reeducating smartphone users, the world’s largest group of technology consumers, about the cost of software.

If the last 20 years have been about making us more productive—sacrificing efficiency and financial sustainability in the process—perhaps the next 20 will be about tackling our collective technical debt, reclaiming efficiency, and improving economic exchange without losing the productivity that’s made software omnipresent in our lives.