As the web grows in popularity and power, so does the amount of data stored and transferred between systems, many of which know nothing about each other. From early on, the format that this data was transferred in mattered, and like the web, the best formats were open standards that anyone could use and contribute to. XML gained early popularity, as it looked like HTML, the foundation of the web. But it was clunky and confusing.

That’s where JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) comes in. If you’ve consumed an API in the last five to ten years, you’ve probably seen JSON data. While the format was first developed in the early 2000s, the first standards were published in 2006. Understanding what JSON is and how it works is a foundational skill for any web developer.

In this article, we’ll cover the basics of what JSON looks like and how to use it in your web applications, as well as talk about serialized JSON—JST and JWT—and the competing data formats.

What JSON looks like

JSON is a human-readable format for storing and transmitting data. As the name implies, it was originally developed for JavaScript, but can be used in any language and is very popular in web applications. The basic structure is built from one or more keys and values:

{

"key": value

}

You’ll often see a collection of key:value pairs enclosed in brackets described as a JSON object. While the key is any string, the value can be a string, number, array, additional object, or the literals, false, true and null. For example, the following is valid JSON:

{

"key": "String",

"Number": 1,

"array": [1,2,3],

"nested": {

"literals": true

}

}

JSON doesn't have to have only key:value pairs; the specification allows to any value to be passed without a key. However, almost all of the JSON objects that you see will contain key:value pairs.

Using JSON in API calls

One of the most common uses for JSON is when using an API, both in requests and responses. It is much more compact than other standards and allows for easy consumption in web browsers as JavaScript can easily parse JSON strings, only requiring JSON.parse() to start using it.

JSON.parse(string) takes a string of valid JSON and returns a JavaScript object. For example, it can be called on the body of an API response to give you a usable object. The inverse of this function is JSON.stringify(object) which takes a JavaScript object and returns a string of JSON, which can then be transmitted in an API request or response.

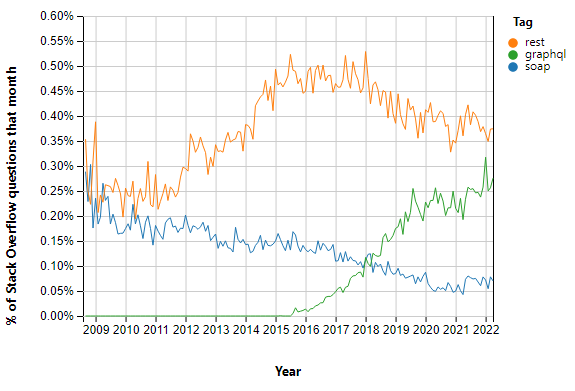

JSON isn’t required by REST or GraphQL, both very popular API formats. However, they are often used together, particularly with GraphQL, where it is best practice to use JSON due to it being small and mostly text. If necessary, it compresses very well with GZIP.

GraphQL's requests aren’t made in JSON, instead using a system that resembles JSON, like this

{

foo {

bar

baz

}

}

Which will return the relevant data, and if using JSON, it will match very closely:

{

"foo": {

"bar": "data",

"baz": "data"

}

}

Using JSON files in JavaScript

In some cases, you may want to load JSON from a file, such as for configuration files or mock data. Using pure JavaScript, it currently isn’t possible to import a JSON file, however a proposal has been created to allow this. In addition, it is a very common feature in bundlers and compilers, like webpack and Babel. Currently, you can get equivalent functionality by exporting a JavaScript Object the same as your desired JSON from a JavaScript file.

export const data = {"foo": "bar"}

Now this object will be stored in the constant, data, and will be accessible throughout your application using import or require statements. Note that this will import a copy of the data, so modifying the object won’t write the data back to the file or allow the modified data to be used in other files.

Accessing and modifying JavaScript objects

Once you have a variable containing your data, in this example data, to access a key’s value inside it, you could use either data.key or data["key"]. Square brackets must be used for array indexing; for example if that value was an array, you could do data.key[0], but data.key.0 wouldn’t work.

Object modification works in the same way. You can just set data.key = "foo" and that key will now have the value “foo”. Although only the final element in the chain of objects can be replaced; for example if you tried to set data.key.foo.bar to something, it would fail as you would first have to set data.key.foo to an object.

Comparison to YAML and XML

JSON isn’t the only web-friendly data standard out there. The major competitor for JSON in APIs is XML. Instead of the following JSON:

{

"hello": "world"

}

in XML, you’d instead have:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" ?>

<hello>world</hello>JSON was standardized much later than XML, with the specification for XML coming in 1998, whereas Ecma International standardized JSON in 2013. XML was extremely popular and seen in standards such as AJAX (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML) and the XMLHttpRequest function in JavaScript.

XML used by a major API standard: Simple Object Access Protocol (SOAP). This standard can be significantly more verbose than REST and GraphQL, in part due to the usage of XML and because the standard includes more information, such as describing the XML namespace as part of the envelope system. This might be a reason why SOAP usage has declined for years.

Another alternative is YAML, which is much more similar in length to JSON compared to XML, with the same example being:

---

hello: worldHowever, unlike XML, YAML doesn’t really compete with JSON as an API data format. Instead, it’s primarily used for configuration files—Kubernetes primarily uses YAML to configure infrastructure. YAML offers features that JSON doesn’t have, such as comments. Unlike JSON and XML, browsers cannot parse YAML, so a parser would need to be added as a library if you want to use YAML for data interchange.

Signed JSON

While many of JSONs use cases transmit it as clear text, the format can be used for secure data transfers as well. JSON web signatures (JWS) are JSON objects securely signed using either a secret or a public/private key pair. These are composed of a header, payload, and signature.

The header specifies the type of token and the signing algorithm being used. The only required field is alg to specify the encryption algorithm used, but many other keys can be included, such as typ for the type of signature it is.

The payload of a JWS is the information being transmitted and doesn’t need to be formatted in JSON though commonly is.

The signature is constructed by applying the encryption algorithm specified in the header to the base64 versions of the header and payload joined by a dot. The final JWS is then the base64 header, base64 payload, and signature joined by dots. For example:

eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLA0KICJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiJ9.eyJpc3MiOiJqb2UiLA0KICJleHAiOjEzMDA4MTkzODAsDQogImh0dHA6Ly9leGFtcGxlLmNvbS9pc19yb290Ijp0cnVlfQ.dBjftJeZ4CVP-mB92K27uhbUJU1p1r_wW1gFWFOEjXk

JSON Web Tokens (JWT) are a special form of a JWS. These are particularly useful for authorization: when a user logs into a website, they will be provided with a JWT. For each subsequent request, they will include this token as a bearer token in the authorization header.

To create a JWT from a JWS, you’ll need to configure each section specifically. In the header, ensure that the typ key is JWT. For the alg key, the options of HS256 (HMAC SHA-256) and none (unencrypted) must be supported by the authorization server in order to be a conforming JWT implementation, so can always be used. Additional algorithms are recommended but not enforced.

In the payload are a series of keys called claims, which are pieces of information about a subject, as JWTs are most commonly used for authentication, this is commonly a user, but could be anything when used for exchanging information.

The signature is then constructed in the same way as all other JWSs.

Compared to Security Assertion Markup Language Tokens (SAML), a similar standard that uses XML, JSON allows for JWTs to be smaller than SAML tokens and is easier to parse due to the use of both tokens in the browser, where JavaScript is the primary language, and can easily parse JSON.

Conclusion

JSON has come to be one of the most popular standards for data interchange, being easy for humans to read while being lightweight to ensure small transmission size. Its success has also been caused by it being equivalent to JavaScript objects, making it simple to process in web frontends. However, JSON isn’t the solution for everything, and alternate standards like YAML are more popular for things like configuration files, so it’s important to consider your purpose before choosing.